When we start building out their home labs, setting up self-hosted services, or soldering together flight controllers for DIY drones, we often complain about physical security mechanisms. We ask why we have to hold down a physical button to flash an ESP32 microcontroller, or why enterprise servers use expensive ECC RAM, or why we have to deal with complex VLAN routing just to watch a movie on Jellyfin. We view these features as corporate bloatware or legacy engineering debt.

We were wrong. Every physical hardware switch, cryptographic boot requirement, and memory isolation boundary exists because of specific, catastrophic Legendary Malwares in the history of computing. These features are the scar tissue left behind by legendary malware. In this post, I am going to break down the exact technical mechanisms of history’s worst exploits.

Table of Contents

The Hardware Killer: CIH and the “Dead Man’s Switch”

The assumption in early computing was that viruses were a storage problem. If your machine got infected, the malware lived on your hard drive. The worst-case scenario involved wiping the disk, reinstalling Windows, and restoring your data from a backup. The physical hardware was considered an immutable, untouchable host. That assumption died in 1998 with the release of the CIH virus, also known as Chernobyl.

The Mechanism of Destruction

CIH did not just delete files; it was one of the first viruses designed to physically “brick” the host machine by targeting the motherboard’s BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) chip.

To understand how CIH achieved this, you have to look at the x86 boot architecture of the late 1990s. When an Intel CPU powers on, it initializes by setting all of its internal registers to zero, except for the Code Segment (CS) register, which is set to all ones. This hardcoded state forces the processor to fetch its very first execution instruction from the 20-bit memory address FFFF:0000, which is located exactly 16 bytes short of the old 1MB memory limit. Motherboard manufacturers mapped this specific memory address directly to the physical BIOS flash memory chip so the computer knew how to wake up its hardware before an operating system was even loaded.

At the time, the industry was transitioning from Read-Only Memory (ROM) to rewritable flash memory chips for the BIOS to allow users to update their firmware easily. However, motherboard manufacturers failed to implement physical write-protection mechanisms on these new chips. Concurrently, the Windows 9x operating system architecture granted user-level applications direct access to the hardware layer (Ring 0 privileges) without any cryptographic verification or strict memory isolation.

CIH exploited this exact intersection of software leniency and hardware negligence. Written by Chen Ing-hau, the virus payload utilized a specific kernel-level command to bypass the operating system and send write instructions directly to the BIOS flash memory, filling the chip with zeros.

When the user turned off their computer and attempted to turn it back on, the CPU queried address FFFF:0000 and found garbage data. Without BIOS instructions, the motherboard could not execute the Power-On Self-Test (POST). It wouldn’t beep, the display wouldn’t initialize, and the machine sat there as dead silicon and copper. Because the software required to re-flash the chip could no longer boot, the only fix was to physically unsolder the BIOS chip from the motherboard, place it in an external hardware programmer, rewrite the firmware, and solder it back onto the board.

The Lesson: The ESP32 BOOT Button

The devastation of CIH forced the industry to realize that software cannot be trusted to protect firmware. Motherboard manufacturers initially responded by adding physical “Write Protect” plastic jumpers to the circuit boards. If the jumper was physically removed by a human, the write-enable pin on the flash chip was left electrically floating, making it physically impossible for any software to overwrite the BIOS, regardless of its privilege level. This eventually evolved into the Secure Boot architecture we use today.

This exact concept dictates how I build DIY drones and sensor nodes in my lab using Espressif ESP32 microcontrollers. When you buy an ESP32 development board, it features two physical tactile switches: EN (Enable/Reset) and BOOT.

When I need to flash new ArduPilot flight controller firmware to the drone, I cannot just send the code over Wi-Fi blindly. The ESP32 relies on specific “strapping pins” to dictate its boot sequence.

| ESP32 Strapping Pin | Default State (Internal Pull) | Condition for Serial Download Mode |

| GPIO0 | Pulled Up (HIGH) | Must be pulled LOW to enter flash mode |

| GPIO2 | Pulled Down (LOW) | Must be left floating or LOW |

| GPIO5 | Pulled Up (HIGH) | Must be HIGH |

| GPIO12 | Pulled Down (LOW) | Must be LOW |

| GPIO15 | Pulled Up (HIGH) | Must be HIGH |

During the initial microseconds of power-on, the ESP32’s immutable ROM bootloader reads the voltage states of these pins. If GPIO0 is HIGH, the chip boots normally from the SPI flash memory. To force the chip into Serial Download Mode so it accepts new firmware, GPIO0 must be physically pulled to ground (LOW) at the exact moment the EN pin is released.

This is the entire purpose of the BOOT button on the circuit board. It is not a design flaw; it is a hardware-level “dead man’s switch.” By requiring a specific, anomalous electrical state on GPIO0, the chip guarantees that a human operator is physically present at the device with their finger on the board.

Even if an attacker finds a remote code execution bug in my drone’s web interface, they cannot overwrite the core bootloader or bypass Secure Boot because they lack the physical fingers to pull GPIO0 to ground during a reboot cycle. You cannot “code around” a disconnected circuit. If your firmware gets corrupted, the hardware demands physical proof of ownership before it allows you to rewrite its core identity.

> [cite_start]BYPASSING BLASTDOOR… [cite: 213]

> EXFILTRATING WHATSAPP_DB…

The Network Wrecking Ball: NotPetya & SMB

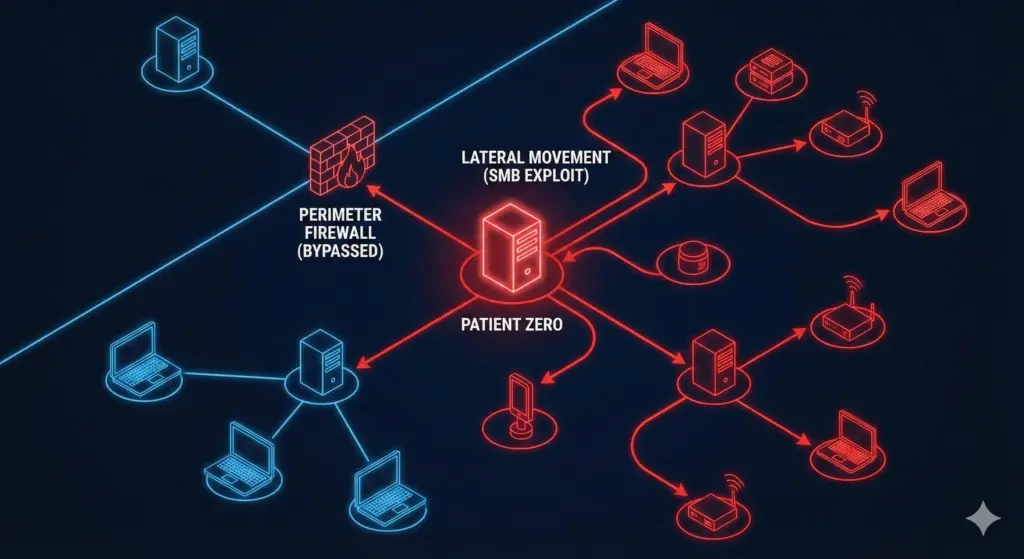

If CIH proved the vulnerability of local hardware, the NotPetya attack of 2017 proved the absolute fragility of unsegmented, flat networks. NotPetya initially presented itself as crude ransomware, displaying a screen demanding Bitcoin to decrypt the victim’s hard drive. However, reverse engineering quickly revealed that the payment mechanism was a facade; NotPetya was actually a “wiper,” a class of malware designed purely to cause irreversible destruction of data.

EternalBlue and Lateral Movement

NotPetya is legendary not just for what it did, but for how fast it did it. It paralyzed global shipping conglomerates and infected roughly 10% of all computer infrastructure in Ukraine in a single afternoon. It achieved this unprecedented propagation speed by chaining together a stolen NSA cyber-weapon called EternalBlue and a credential-dumping tool called Mimikatz.

The vector of attack was the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, specifically SMBv1, which handles native Windows File Sharing over TCP Port 445. EternalBlue exploited a severe vulnerability (MS17-010) in how the Windows kernel processed “Extended Attributes” (FEA) inside incoming SMB packets.

When a Windows server received an SMB packet, the kernel function SrvOs2FeaListSizeToNt calculated how much memory to allocate for the data. The fatal math error was that Windows relied entirely on the packet’s declared size rather than inspecting the actual payload size. An attacker could send a malformed packet stating, “I have 50 bytes of data.” The Windows kernel would dutifully allocate exactly 50 bytes in the highly privileged Kernel Pool. The attacker’s packet, however, contained significantly more data. This excess data spilled over the allocated boundary, causing a massive Kernel Pool Buffer Overflow.

Because this overflow occurred within kernel memory rather than user space, the injected code was executed with System privileges – the absolute highest level of access on a Windows machine, bypassing all user-level access controls entirely.

Once EternalBlue cracked the front door of a single machine, NotPetya dropped Mimikatz into the system. Mimikatz aggressively scraped the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) residing in the host’s volatile RAM. It looked for the plaintext passwords or hash credentials of any user who had recently authenticated to that specific computer.

This is where the flat network topology became a fatal flaw. In a typical corporate environment, IT administrators log into various machines across the network to perform maintenance. If a domain admin had logged into the machine that NotPetya just compromised, Mimikatz stole their highly privileged credentials directly from the RAM. NotPetya then used those legitimate administrative keys to instantly authenticate to every other machine on the local network, bypassing firewalls and antivirus entirely because it was logging in as the boss.

The Lesson: Subnets and VPNs

Running a home lab in Pilani means my network is a chaotic mix of devices. I have an old, rooted OnePlus 3T running a lightweight Linux stack serving as a network dashboard , a dedicated NAS appliance hosting terabytes of data, and a Jellyfin media server so my friends can stream movies. Because I use SMB/CIFS to transfer files between my laptop and the NAS, Port 445 is actively listening on my network.

The lesson of NotPetya is brutal and uncompromising: If you leave Port 445 open to the public internet, you deserve what happens next.

SMB was engineered in an era of high-trust Local Area Networks (LANs). It was never designed to withstand the hostile environment of the public internet. Exposing it via port forwarding on your edge router is a catastrophic architectural failure. To prevent a NotPetya-style lateral wipeout in a home lab, you must implement enterprise-grade network segmentation.

- VLAN Segmentation: Your home network cannot be a single

/24subnet where every device can ping every other device. You must configure Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) at the switch level. I run a “Guest” VLAN for my friends’ phones and sketchy smart TVs, completely isolated from my “Server” VLAN. The firewall rules on my OPNSense router explicitly drop any packets attempting to route from the Guest subnet to Port 445 on the Server subnet. - Overlay Networks (VPNs): When I am away from home and need to access my SMB file shares or the Jellyfin server, I do not open ports on the firewall. I broker the connection through a secure overlay network like Tailscale or WireGuard. This guarantees that only devices with cryptographic keys can even attempt to initiate a TCP handshake with my internal server.

Furthermore, unique credential management is mandatory. If you use the same local administrator password for your Proxmox hypervisor, your TrueNAS box, and your desktop PC, you are replicating the exact failure condition Mimikatz exploited. If one box falls, they all fall.

TL;DR Lesson

The SMB protocol is highly complex and historically vulnerable to kernel-level buffer overflows. Exposing file sharing ports to an untrusted network invites total system compromise. VLANs and VPNs are not enterprise bloatware; they are mandatory physical and logical barriers that prevent a compromised device from laterally wiping your entire home lab.

The IoT Nightmare: Mirai & Default Passwords

While NotPetya required stolen military-grade zero-day exploits to breach networks, the Mirai botnet of 2016 nearly collapsed the internet backbone using nothing but raw speed and manufacturer stupidity. Mirai ignored Windows PCs and enterprise servers entirely. Instead, it targeted the Internet of Things (IoT) – specifically cheap Linux-based IP cameras, home routers, and Network Video Recorders (NVRs).

Stateless Scanning and the Dictionary Attack

To understand why Mirai was so devastating, you have to understand how network scanning works. Traditional scanners, like Nmap, operate statefully. To check if a port is open, the OS network stack initiates a full TCP 3-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK), allocates system memory to track the connection state, and waits for specific timeouts. This is reliable, but it is incredibly slow and resource-intensive.

Mirai utilized Stateless TCP Scanning. The malware bypassed the OS network stack entirely and crafted raw TCP SYN packets. It fired these packets at Telnet ports (Port 23 and 2323) targeting random IP addresses across the internet at the maximum physical speed the network interface card could handle.

Crucially, the scanner did not allocate any memory to remember which IP addresses it had queried. It simply blasted packets out and listened passively on the interface. If a SYN-ACK packet happened to arrive, the malware instantly knew it had found a live target, completed the handshake, and initiated the attack phase.

Because it required almost zero memory overhead, a single infected security camera could scan massive portions of the global IPv4 address space in minutes. Once Mirai connected to a live Telnet port, it did not deploy a sophisticated buffer overflow. It simply executed a dictionary attack using a hardcoded list of 62 default username and password combinations that manufacturers lazily shipped with their hardware.

| Common Mirai Dictionary Targets | Target Device Profile |

admin / admin | Generic consumer network routers |

root / 123456 | Generic IoT appliances and DVRs |

root / xc3511 | Default credentials for Chinese white-label IP cameras |

If the login succeeded, the Mirai Command & Control (C2) server authenticated to the device, ran a basic wget command, downloaded the malicious binary directly into the device’s volatile RAM, and enslaved it.

Mirai featured a fascinating anti-persistence mechanism: the malware lived exclusively in RAM. It never wrote itself to the flash storage. If you unplugged the infected camera and plugged it back in, the virus was wiped completely. However, this didn’t matter. Because the stateless scanning swarm was so massive and fast, your newly rebooted camera would be scanned, brute-forced, and reinfected within five minutes of coming back online.

Mirai enslaved over 600,000 devices. It synchronized this massive botnet to launch a 1.2 Tbps DDoS attack against the DNS provider Dyn, effectively knocking Netflix, Twitter, Reddit, and large portions of the internet offline.

The Lesson: Air-Gapping Frigate NVR Cameras

Living in a rural area means dealing with local wildlife, stray dogs, and monitoring the perimeter. For this, I use Frigate NVR, an open-source network video recorder featuring local AI object detection. The video feeds come from a dozen inexpensive IP cameras sourced directly from AliExpress.

These cameras are functionally identical to the hardware Mirai targeted. They run outdated Linux kernels, feature undocumented Telnet services, and aggressively attempt to “phone home” to cloud servers in China to offer P2P streaming features. If I plug one of these cameras directly into my main network and fail to change the admin/admin password, it will be compromised before I finish mounting it to the wall.

To mitigate the Mirai threat model, you cannot rely on software firewalls on the camera itself. You must enforce physical and logical quarantine:

- The NoT VLAN: IoT devices must be segregated into a “Network of Things” (NoT) VLAN. This subnet must have its default gateway routing strictly controlled. It is denied access to the public internet and explicitly blocked from initiating connections to my trusted management LAN.

- Dual-NIC Isolation: For absolute security, the server hosting the Frigate Docker container is equipped with two physical Network Interface Cards (NICs).

NIC 1connects to my trusted LAN for dashboard access.NIC 2connects physically to an unmanaged PoE (Power over Ethernet) switch that powers the cameras. The cameras exist on a completely disjointed physical network. They literally do not possess a physical copper path to the internet router. - Internal Restreaming: Because these cheap cameras have weak SoCs that overheat and crash if multiple clients request video streams, I configure Frigate to use

go2rtc. Frigate acts as a proxy, pulling a single RTSP stream from the camera over the isolated NIC, and restreaming it internally to Home Assistant.

TL;DR Lesson

IoT devices are effectively disposable Linux computers with horrific security postures. Stateless scanning guarantees that any exposed device with default credentials will be compromised globally in minutes. Untrusted hardware must be quarantined in dedicated VLANs with zero internet routing, forcing all communication through secured, dual-NIC proxy servers.

The Murderous Controller: Triton & The Safety Gap

Botnets take websites offline, and wipers destroy hard drives. But the Triton (also known as Trisis) malware discovered in 2017 represented a terrifying escalation in cyber warfare: it was explicitly designed to cause a kinetic explosion and kill human beings.

> VALVE OPEN: 100%

Attacking the Safety Instrumented System

Triton targeted Industrial Control Systems (ICS) in petrochemical facilities, specifically focusing on the Safety Instrumented System (SIS) manufactured by Schneider Electric (the Triconex line).

In industrial engineering, the SIS is the absolute final line of defense. It is an autonomous array of computers whose sole operational purpose is to prevent a disaster. Its logic is immutable: If the temperature in the reactor exceeds critical limits, immediately close the intake valves to prevent an explosion.

Triconex controllers do not run standard Windows or Linux. They operate on bare-metal firmware using Triple Modular Redundancy (TMR). The hardware consists of three separate PowerPC MPC860 processors that independently execute the safety logic and “vote” on the outcome. If one CPU glitches due to a cosmic ray, the other two outvote it, ensuring maximum fault tolerance.

The attackers did not use a traditional buffer overflow. They reverse-engineered the proprietary TriStation Protocol, which the plant engineers used to program the controllers over UDP Port 1502. Triton simply emulated the behavior of legitimate engineering workstation software.

The malware connected to the controller, uploaded the current firmware, and located the “execution table” – the specific memory map where the PowerPC CPU looks to find its next sequence of instructions. Triton injected a malicious jump command into this table, pointing the CPU to a blank sector of memory where the attackers had deposited a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) payload.

The objective was catastrophic: deploy the RAT to completely disable the safety logic, effectively cutting the wires to the emergency stop buttons. Concurrently, the attackers planned to manipulate the plant’s primary operational controllers to intentionally ramp up the physical pressure in the pipes, leading to a massive physical explosion because the safety system was blind.

The attack failed, but not because of firewalls or antivirus software. The attackers made a syntax mistake in their pointer arithmetic. When the malware attempted to write data to an invalid memory address, it triggered a “System Fault” on the PowerPC processor. Because the entire hardware architecture was explicitly designed for safety, the controller interpreted the memory crash as a critical hardware failure and instantly triggered a plant-wide emergency shutdown. The plant survived because the physical safety protocols defaulted to an “off” state when confused.

The Lesson: Solar Racks and Physical Breakers

The engineering philosophy targeted by Triton applies directly to the high-power infrastructure sitting in my Pilani lab. Powering the servers, cameras, and cooling fans during Rajasthan’s frequent grid blackouts requires a serious energy setup. I run a Luminous solar inverter connected to a massive DIY rack of LiFePO4 batteries.

A battery bank of this size is capable of outputting hundreds of amps of direct current instantly. If a short circuit occurs, that much current will instantly fuse copper cables, melt busbars, and cause a devastating electrical fire.

To monitor this system, I built a custom data logger using an ESP32 microcontroller and an RS-485 to UART adapter (using the MAX485 chip). By tapping into the inverter’s Modbus RTU interface over the differential RS-485 serial lines, I can read the holding registers to track PV voltage and battery state of charge (SOC).

Because Modbus RTU lacks authentication, I can also write to these registers. A Python script running in my Home Assistant dashboard can send a Modbus command to switch the inverter from battery power to grid power, or command the system to shut down entirely.

However, applying the lesson of Triton means realizing a terrifying truth: Software is not safety.

Relying on a Home Assistant automation script to monitor battery voltage and send a Modbus “off” command to prevent a fire is a catastrophic violation of engineering principles.

- The ESP32 running the Modbus polling could experience a memory leak and crash.

- The Wi-Fi network could drop packets due to RF interference.

- A bad OTA update could brick the Home Assistant container.

- An attacker could compromise the network, access the Modbus bus, and deliberately alter the battery charging voltage limits, identical to the Triton threat model.

This highlights the absolute separation between Control Logic and Safety Logic. Control logic (the ESP32 and Home Assistant) makes the system efficient and provides pretty graphs. Safety logic prevents the system from burning the house down.

In my solar setup, the final defense mechanism relies entirely on physics. I have an oversized, 125-Amp DC Circuit Breaker physically wired in series between the LiFePO4 battery bank and the inverter. If the inverter’s internal software faults and attempts to draw 150 Amps, the Modbus software cannot bypass the breaker. The physical copper inside the breaker will heat up, the bimetallic strip will warp from the thermal load, and the mechanical spring will forcefully sever the connection, breaking the DC arc.

TL;DR Lesson

Never mix operational control logic with hardware safety logic. Software bugs, network latency, and malware can crash a microcontroller, but they cannot rewrite the laws of thermodynamics. Any system capable of causing physical destruction must feature a hardware-level safety disconnect (like a mechanical circuit breaker) that operates entirely independently of the software stack.

The Physics Hack: Rowhammer & ECC RAM

The fundamental assumption in computer science is that software and hardware exist in separate, non-overlapping domains. An operating system might crash, but it cannot physically alter the state of the RAM chip without using the proper memory allocation channels. That assumption was completely dismantled by the discovery of the Rowhammer vulnerability in 2014. Rowhammer is technically a software exploit, but it operates by weaponizing the physical properties of silicon at the subatomic level.

Crosstalk and the Bit Flip

Modern Synchronous Dynamic Random-Access Memory (SDRAM), particularly DDR3 and DDR4, is manufactured with incredibly high density. Millions of microscopic capacitors are packed tightly together on the silicon die. Each capacitor holds a tiny electrical charge representing a single data bit (a 1 or a 0).

When the CPU needs to read data, the memory controller applies a high voltage to a “Wordline” to activate a specific row of memory, reads the data out through the perpendicular “Bitlines,” and then closes the row. Because these capacitors are situated nanometers apart, applying high voltage to a single row causes a minute amount of electromagnetic interference – known as Crosstalk – to bleed into the adjacent, neighboring rows.

Under normal operating conditions, this leakage is negligible, and the RAM controller’s refresh cycle recharges the capacitors before any data is lost. However, security researchers discovered that if an attacker could force the CPU to activate and deactivate a single row of memory at an extreme velocity – roughly one million times per second – the rapid fluctuation of voltage would cause the adjacent rows to leak charge significantly faster than the refresh cycle could replenish it. Eventually, a capacitor in the adjacent row would lose enough charge that the computer would read a 1 as a 0. This physical degradation of data is known as a Bit Flip.

To execute this, attackers had to overcome a major hurdle: the CPU Cache (L1/L2/L3). If the CPU kept the memory row in its high-speed internal cache, the physical RAM module would never experience the voltage fluctuation. Attackers bypassed this optimization by writing tight assembly loops utilizing the CLFLUSH (Cache Line Flush) instruction.

MOV (Address_X) ; Read from DRAM Row A

MOV (Address_Y) ; Read from DRAM Row B

CLFLUSH (Address_X) ; Force CPU to drop Row A from Cache

CLFLUSH (Address_Y) ; Force CPU to drop Row B from Cache

JMP top ; Repeat 1,000,000 times/secBy aggressively “hammering” rows A and B, the attackers forced the physical row situated geographically between them (Row C) to leak charge until a bit flipped.

To turn this physics glitch into an actual system exploit, attackers utilized a technique called “Memory Spraying.” They filled the computer’s RAM with Page Tables -the operating system’s internal map dictating which memory addresses belong to secure “Kernel Space” and which belong to unprivileged “User Space”. By meticulously calculating the geometry of the RAM chip and hammering specific addresses, they could reliably flip a bit inside a Page Table Entry (PTE). Changing a single bit in a PTE pointer could instantly transform a read-only user segment into a read/write kernel segment. Suddenly, a malicious JavaScript payload running inside a sandboxed web browser tab possessed raw, physical read/write access to the entire machine’s RAM.

> WAITING FOR INPUT…

The OnePlus 3T Server and the ECC Requirement

Within my home lab environment, I repurpose older Android hardware to run low-power Linux services. Specifically, I use a rooted OnePlus 3T running a Debian environment via Termux. Sitting on my desk, it draws barely any power while compiling code or routing DNS traffic. It contains a potent Snapdragon 821 processor and 6GB of LPDDR4 RAM.

However, the OnePlus 3T, like almost all consumer laptops, smartphones, and desktop PCs, utilizes standard, non-ECC memory. Because it lacks Error Correcting Code logic, it is fundamentally vulnerable to Rowhammer.

In a data center or enterprise environment, servers are mandated to use ECC RAM. ECC memory modules include an extra memory chip on the DIMM board designed to store cryptographic parity bits. When a memory row is read, the memory controller calculates the parity of the data and checks it against the stored ECC bits. If a cosmic ray or a Rowhammer attack causes a single bit to flip, the ECC algorithm detects the mathematical anomaly and automatically flips the bit back to its correct state before handing the data to the CPU.

While advanced academic exploits (like the ECCploit and TRRespass papers) have demonstrated highly theoretical methods to overcome ECC by causing precise multi-bit flips simultaneously , standard ECC memory completely neutralizes 99% of real-world Rowhammer techniques. This illustrates the fundamental divide between consumer-grade equipment and enterprise architecture. The OnePlus 3T is reliable enough to make a phone call or host a local Python script; an enterprise server with ECC RAM is reliable enough to host a bank’s database without fear of subatomic silicon physics betraying the operating system.

TL;DR Lesson

Hardware is subject to the laws of physics. Rowhammer proved that memory isolation mechanisms in the OS can be bypassed purely by manipulating electrical crosstalk in dense silicon. For mission-critical infrastructure, consumer-grade non-ECC RAM is mathematically incapable of guaranteeing data integrity against advanced microarchitectural exploits.

Conclusion

To fully appreciate why modern processors and operating systems impose such draconian limitations on code execution, you have to look back to the inception of the network worm. In 1988, the Morris Worm inadvertently crippled the early ARPANET, essentially taking down the infant internet.

The worm exploited a fundamental flaw in the C programming language: the gets() function. The Unix fingerd daemon utilized gets() to read user input, but the function contained no boundary checking – it simply accepted data until it saw a carriage return. Morris sent a 536-byte string to a buffer only designed to hold 512 bytes.

The excess 24 bytes spilled out of the allocated memory space and overwrote the adjacent stack frame, specifically targeting the Instruction Pointer (EIP) Return Address. Instead of the program crashing, the overwritten return address instructed the CPU to jump backward into the buffer itself. Inside that buffer, Morris had placed compiled VAX machine code containing the command execve("/bin/sh", 0, 0), which spawned a root shell over the network.

This Buffer Overflow technique remained the absolute gold standard for hackers for decades. It relied on the fact that the CPU could not distinguish between “Data” (text input) and “Instructions” (executable code) if they were loaded into the same memory space.

The industry’s response to the buffer overflow crisis was the implementation of the NX Bit (No-eXecute), also known as Data Execution Prevention (DEP). Hardware manufacturers updated processor microarchitecture to add a flag to the memory Page Tables. The operating system could now explicitly mark memory segments as “Data Only”. If an attacker successfully executed a buffer overflow and attempted to force the CPU’s instruction pointer into the buffer to run shellcode, the CPU would check the NX Bit for that memory page. Recognizing it was marked as non-executable data, the CPU would throw a hardware exception and immediately terminate the process, neutralizing the attack.

The existence of the NX bit, much like the requirement for Secure Boot keys, the implementation of ECC RAM parity checks, and the physical BOOT buttons on microcontrollers, is a direct, physical manifestation of historical software trauma.

The modern technology stack is heavily insulated. It is incredibly easy for makers and home lab operators to trust the abstractions provided by Docker containers, high-level languages like Python, and automated dashboards. However, analyzing the history of legendary malware-from CIH erasing firmware, to NotPetya exploiting kernel memory allocation, to Rowhammer weaponizing silicon physics – reveals a cynical truth: the ultimate security boundaries are physical.

Security features are not arbitrary engineering decisions. They are the accumulated scar tissue of catastrophic failures. They exist because the industry learned, at massive financial and operational cost, that software is fundamentally incapable of protecting itself from a sufficiently motivated adversary.

As you build out your own home labs, write custom code for your drones, or wire up massive solar arrays, you must audit your infrastructure through this cynical lens. Is your “air gap” purely logical (a VLAN rule), or is it physical (a completely separate switch)? If an automation state hangs, is there a physical watchdog timer or dead-man switch to interrupt power? Is the safety of a high-voltage battery system reliant on a script, or is it guaranteed by a physical circuit breaker? By grounding network design in the absolute realities of physics and acknowledging the historical vulnerabilities of software, we ensure our infrastructure doesn’t just operate efficiently – it fails safely.